Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

The successful way that India holds elections has become a new part of the country’s ‘soft power’ and foreign policy. But the illicit use of money in campaigning is yet to be stamped out.

Nevertheless the Election Commission of India (ECI) does manage to hold generally peaceful, transparent and fair elections for 834 million eligible voters, ensuring that everyone from the illiterate to those living in the remotest parts of the country including on the tops of mountains, in deep forest and on islands closer to Indonesia than India, can cast their vote in what was, this year, the world’s largest election.

That was the premise of the book, An Undocumented Wonder: The Making of the Great Indian Election, written by Dr S Y Quraishi, former Chief Election Commissioner of India, which was published last month. Dr Quraishi gave a talk about the book inside The Gandhi Hall of India House in London. The High Commissioner of India to the UK HE Mr Ranjan Mathai and Lord Desai were among the dignitaries present.

Dr S Y Quraishi talks about his book at the High Commission of India, London

Mathai said that the way that India conducts its elections has become an inspiration to the world, it was now part of India’s “soft power” and a USP in the country’s foreign policy. “The undocumented wonder is the wonder of the organisation of the Indian election which is being recognised worldwide,” he said, adding many Commonwealth and African countries wanted to learn from India.

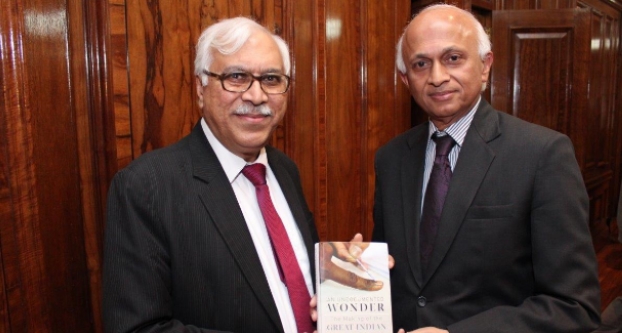

Dr S Y Quraishi (left) holds his book, which analyses the wonder of the Indian election process, together with HE Mr Ranjan Mathai (right)

Quraishi, who retired as Chief Election Commissioner of India in 2012, said: “We have to reach every single voter in every corner of the country. We have voters at 16,000 feet [above sea level], in deep forest and on islands, as well as in the desert. We have to reach every one of them. Every voter should access to a polling station. There are places where you have to walk three days to get to a polling station,” he said.

He pointed out that India is one of the most diverse countries in the world with 22 official languages, 200 regional languages and 6,000 dialects, with everything from tribal warfare to Maoist militancy to contend with. All of this needs to be taken into account when planning the election.

Quraishi, who first became Election Commissioner in 2006, said: “I have seen bomb blasts and people trying to create disturbances at polling stations – but all that is history and people would not dare do that now. If anything like that happens we do a repoll four to five days later with all our reinforcements and so they know there is no point in trying. One pillar of our strength is the Indian media who are our eyes and ears. If they see any malpractice or violation of the Model Code of Conduct for the guidance of political parties and candidates, they report on it and our officers are told to commence action the minute they see any media report.”

There were 931,000 polling stations and 1.7 million electronic voting machines that had to be got ready for the 2014 general election, which was conducted by 11 million ‘babus’ (Indian bureaucrats). “It takes a thief to catch a thief,” he said explaining the babus knew best the kinds of tricks to watch out for.

The number of voters is staggering too.

“By 2012 there were 180 million more voters than in the 2009 general election, “ Quraishi said. “That is four Australias and 10 Portugals or 20 Finlands; or that is three South Africas and two Cambodias,” he pointed out.

Five hundred and fifty million Indians or 65 per cent of the electorate voted in the 2014 election – which was a record turnout for India. “Two months before this election I predicted it would be the highest turnout ever. Turnout is very important and part of democracy. If candidates are selected with just 15 per cent of voters casting a vote their legitimacy is brought into question, so low turnout has implications for the whole system,” he added.

He said some people had suggested compulsory voting was the solution but in this election that would have meant 300 million odd cases flooding the courts. “Now there are 10 million cases flooding the courts. We can’t add another 300 million!” he told the audience.

Electronic voting was first introduced in the 2004 national elections and the simple machines have become a huge success because there is no dispute over the results and candidates accept them, even if they lose by just one vote.

Rajasthan state Congress president C P Joshi lost his seat by one vote to BJP rival Kalyan Singh Chouhan in the Nathdwara constituency in Rajasthan in the 2008 Assembly Elections. “The side story is that his wife and daughter did not vote,” Quraishi said, emphasising how every vote counted. Prof Joshi later fought and won the Lok Sabha election from the Bhilwara district and in 2012 the Assembly results were in fact found to be void as Singh’s wife had voted twice.

Another advantage of the machines (which Quraishi describes as low technology and nothing more than a 17th century elementary calculator) is that even the illiterate can use them and press a button which has the candidate and his or her party’s symbol on. “We used to have 1000s of invalid voting slips and disputes. All that is history – now there are zero invalid votes,” he said.

Another major achievement of the ECI is that it is the one institution that Indian politicians respect. “If Indian politicians are scared of someone, it’s the Election Commission because of the credibility it’s acquired over the years,” he said.

“Indian voters are the smartest voters in the world. Ask any losing politician and they will back me up.”

The ECI controls noise levels and defacement of property too. “In fact, some people complain we have killed the festival of democracy and replaced it with the silence of a graveyard,” he said. “We do vulnerability mapping – we look for criminals in an area – and know who they are – and deploy forces beforehand.” He spoke about how some criminals “enjoyed political patronage” and had arrest warrants out for them. “Six months before the elections we say we want these warrants to be zero. We also keep video cameras on candidates that we know might cause problems 24/7,” he added.

He said the Election Commission also took an active role in wiping out voter apathy, especially in urban areas where “the urban educated often brag about not voting, saying things like, ‘All politicians are thieves’ or ‘I have never voted in my life’. We tell them, ‘All leaders are not thieves and we have become a major power because of this.’”

For the first time in 2014 there was an option on the voting slip called ‘None Of The Above.’ The idea of this, he said, was that those armchair critics who did not vote, could now come out and express their anger.

He also spoke about the highly successful and effective Pappu TV campaign launched to wipe out apathy.

He said the Commisison had also spent recent years educating youth and women making sure they realised they had the right to vote, as historically these groups had lower turnout. The Election Commission introduced National Voter’s Day on 25 January, a day before Republic Day, and has closed the gender gap to just 1.6 per cent.

“We have had equal voting rights for women from Day 1. The USA took 144 years. The UK took 100 years. We are a poor country and we gave this from Day 1, even despite illiteracy,” he said.

The title of the book was, he explained, inspired by a journalist who had written an article heavily criticising the ECI who then went and saw the Indian election machine with his own eyes and was blown away. “ECI is the most self-effacing organisation, and the Indian election is an undocumented wonder!” he wrote.

Dr S Y Quraishi signs his book

In response to an audience question, Quraishi said the reason the election took six weeks to conducted was to “protect lives.” Hundreds of thousands of armed security personnel were needed to protect polling stations and candidates and it was impossible for them to be everywhere at once so it had to be carefully planned. Indian elections can be blighted by attacks by Maoist insurgents and others. “I don’t see why people complain. The voters only have to vote once. The media gets so much tea [covering it]. It’s only the politicians who have to work all the time,” he said.

As for why some Indian citizens were surprised to fine they were not registered on polling day, he said: “The electoral role can never be perfect. It is a dynamic process. People were told to check the electoral roll in different languages. But gated communities did not open their gates and people set their dogs on the census takers visiting them.”

He explained that non-resident Indians (NRIs) had had the right to vote since 2008 but only if they returned to India and voted as a resident in the constituency where they were registered. He said there had been surprisingly little take-up of this. “We were worried there would be enormous response but it was lukewarm,” he said. In the 2012 Punjab state assembly elections only three NRIs registered to vote.

NRIs may not vote by post, online or at Indian Missions abroad.

“The technology for distance and Internet voting is not dependable,” he explained.

But black money [money earnt on the black market on which taxes are not paid] and bribes being used in campaigns are still the bane of the ECI’s existence.

Quraishi admitted: “We do have problems with the use of black money. It’s a major problem. We have tried to deal with it and made life really miserable for those politicians. Money power disturbs the level playing field because there is a ceiling to how much can be spent on campaigning and it is the one thing we cannot control. We have done our best to make people’s lives miserable,” he said, explaining they had even raided a wedding which was a front for a campaigning exercise and no bride and groom were present.

“Business people complained at this last election that the Election Commission kept stopping cars searching for black money and then, if we found any, they said they worked in the diamond trade. We don’t know what the solution is except to be even more rigid.”

naomi.canton@asiahouse.co.uk

To read more articles on the Indian elections click here.

To read or listen to what Indian economist and Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen spoke about when he visited Asia House in June 2014, click here.