Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

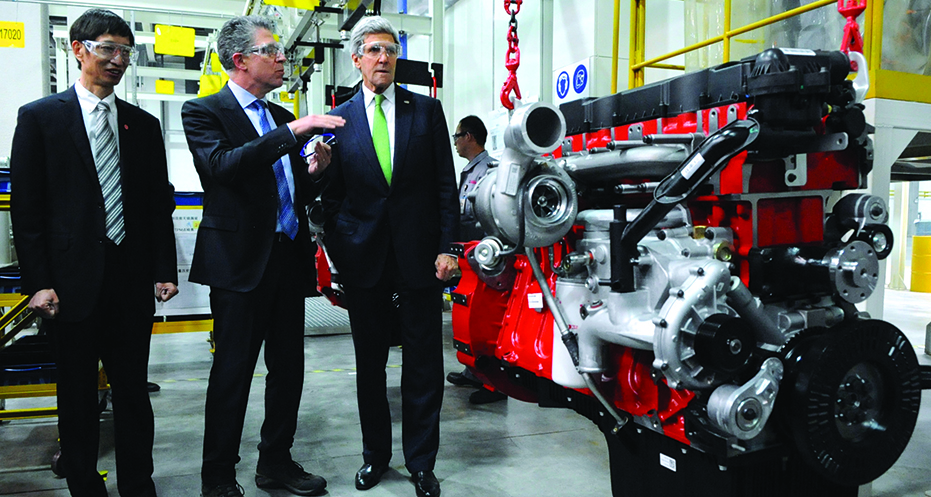

John Kerry touring an auto factory in China when he was US Secretary of State. Current US trade measures against Beijing have been interpreted in some quarters as an attempt to check China’s progress in high tech manufacturing.

Asia House’s publication, Asia House Insights: Asia Trade in the New Global Order, brings together the thoughts of leading figures in global trade. Here, Ravi Velloor, Associate Editor, The Straits Times, considers the wider context of the current US-China trade tensions.

Seven decades ago, shortly after World War II wound to a close, the American diplomat George F. Kennan wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs magazine on a way for the United States to tackle the Soviet Union that later came to be famously known as ‘containment policy’. Lying between the extremes of appeasement and war, Mr Kennan advocated containment – and a Cold War rather than a hot, military conflict. In his view, Joseph Stalin was not Adolf Hitler, with a fixed timetable for conquering Europe. However, he was determined to dominate the continent. If Soviet expansionism could be contained for a long enough time, and with a coherent strategy, it could eventually even lead to a state collapse because of Soviet society’s many internal contradictions, Mr Kennan argued.

Seven decades ago, shortly after World War II wound to a close, the American diplomat George F. Kennan wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs magazine on a way for the United States to tackle the Soviet Union that later came to be famously known as ‘containment policy’. Lying between the extremes of appeasement and war, Mr Kennan advocated containment – and a Cold War rather than a hot, military conflict. In his view, Joseph Stalin was not Adolf Hitler, with a fixed timetable for conquering Europe. However, he was determined to dominate the continent. If Soviet expansionism could be contained for a long enough time, and with a coherent strategy, it could eventually even lead to a state collapse because of Soviet society’s many internal contradictions, Mr Kennan argued.

Fast-forward to March 2015 and check out the paper published by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) labelled ‘Revising US Grand Strategy Toward China.’ Coauthored by former US ambassador Robert Blackwill and the strategic affairs expert Ashley Tellis, it also draws upon expert knowledge by a study group. Topping the list of scholars in the group is Graham Allison, the Harvard professor known around the world for coining the phrase Thucydides Trap – his characterisation of situations where entrenched powers inevitably clash with a rising challenger in their attempt to maintain dominance.

“Because the American effort to ‘integrate’ China into the liberal international order has now generated new threats to US primacy in Asia – and could result in consequential challenges to American power globally – Washington needs a new grand strategy towards China that centres on balancing the rise of Chinese power, rather than continuing to assist in its ascendancy,” Blackwill and Tellis wrote. Interestingly, the paper was published almost exactly a decade after then US Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick first called for China’s actions to be tested against the touchstone of whether it was a “responsible stakeholder” in the international system, or not. It also came months after Chinese President Xi Jinping made his ‘Asia for Asians’ speech, where he argued that “Asia’s problems must ultimately be resolved by Asians and Asia’s security ultimately must be protected by Asians.”

Concluding that China was no longer a responsible stakeholder, Blackwill and Tellis went on to suggest that “only a fundamental collapse of the Chinese state would free Washington from the obligation of systematically balancing Beijing, because even the alternative of a modest Chinese stumble would not eliminate the dangers presented to the United States in Asia and beyond.”

The diplomat-scholar pair did not recommend containment “because of the current realities of globalisation” but then proceeded to prescribe a series of measures that, in sum, amount to just that. They suggested that the US revitalise its economy, expand Asian trade networks and exclude China from them, create a Technology Control Regime, implement effective cyber policies, reinforce Indo-Pacific partnerships and energise high-level diplomacy with China. The report lay largely buried as long as the highly cerebral Barack Obama, with his sophisticated world view and tolerance towards power shifts, held the presidency. It is said that CFR president Richard Haass himself was not convinced about the paper’s thesis but nevertheless allowed its publication in order to prompt debate.

However, it does seem as though influential sections in the Trump administration have dusted off the Blackwill-Tellis report and decided to make it their playbook. With all the four key pillars of the US government – the White House, State Department, the Pentagon and Treasury – now aligned on the matter of checking China, the situation could be more serious than most realise. For any strategy of containment in all but name will spark counter-measures that raise the risk of full-blown conflict.

How did things get to such a pass that another Thucydides Trap moment seems almost inevitable? Current common knowledge would suggest that President Donald Trump is breaking away from a line set down by eight former presidents, starting with Mr Richard Nixon whose landmark 1972 visit to Beijing set up the rapprochement that would endure for so long. Yet, transcripts of White House tape recordings during the Nixon presidency tell us another story. In one meeting with Mr Nixon, held on 14 Feb 1972, weeks before the Nixon-Mao summit, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger says he expects the US-China relationship to sour again in 20 years and the US would have to lean towards Russia to discipline China.

“The Chinese,” Dr Kissinger tells Mr Nixon, “are just as dangerous [as Russians]. In fact, they are more dangerous over a historical period.” Chinese tact, and Deng Xiaoping’s advice to lie low, probably extended the honeymoon period with the US beyond the predicted two decades. But neither was Beijing walking about in a trance about its own security vis-a-vis America. The 1974 grab of the Paracels from Vietnam when the Nixon administration was paralysed by the Watergate scandal, and the surprise seizure of Mischief Reef from the Philippines in 1995, three years after the US vacated Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Base, underscored the canniness and determination with which China set about preparing to protect its soft underbelly. Each time, the affected country and the broader region dismissed these events as one-off things.

Things began to change at the turn of the century when the US Department of Defence, or Pentagon, began to exhibit significant China worry. Visiting Asian military delegations were often confronted with questions on how they intended to tackle a rising and assertive China, surprising the Asians with the depth of their concern. The State Department always had a more nuanced view of the world, but successive Secretaries of State from Ms Condoleezza Rice onwards have cast a sceptical eye on China. In the current context, though, it was Treasury’s attitudinal turn that made the difference. A lot of it was caused by Wall Street’s complaints that US companies were unfairly treated in China and that their operating margins on the mainland were steadily declining.

But there is another factor: the fear that, in today’s world, technology tends to be a ‘winner-takes-all’ game and that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Vision 2025 was nothing but a sophisticated move to dominate the world through a leap in technology.

Mr Trump’s recent “we are winning” boasts come from seeing his actions on trade with China beginning to hurt the Chinese economy, the valuations of Chinese companies such as Alibaba that depend on external markets for future growth, and, more importantly, sentiment around everything China. Beijing’s move to initiate what looks like measures to prop up the economy and an easing up on environmental standards for industry as the winter months approach relays its own concerns about its vulnerability. On the other hand, its recent aggressive moves in the South China Sea against the passing destroyer USS Decatur, and cancellation of high-level military talks, suggest that the last thing on its mind is abject debasement of itself or a wholesale capitulation to US demands.

There is no reason to crow at Beijing’s discomfiture: a plunging yuan hurts the competitiveness of Asian exporting nations and fewer checks on Chinese pollution affect the whole world. These are not happy times. Wall Street is beginning to reflect its concern over the emerging situation. On 10 October, US stocks had their biggest fall since February, led by technology and industrial companies, largely on the jump in US interest rates but also because of the frictions with China.

For the first time in two decades, we are seeing the unusual occurrence of stocks and bonds, which usually have an inverse relationship, falling together. These are phenomena that might yet place a cautionary check on Mr Trump’s hand at some point. For now though, and that includes the prevailing sentiment at the US IndoPacific Command in Honolulu, the mood is jingoistic. From Australia to Japan and India, no power relishes the thought of being asked to choose sides; in fact, most are rushing to get out of the way. The last weeks of the Malcolm Turnbull government signalled a desire to repair the friction points in the Australia-China ties, and Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently travelled to Beijing for a summit with President Xi Jinping. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi travelled to Wuhan in May for two days of fence-mending talks with President Xi.

If containment of China is indeed what the US is pursuing, it is unlikely to succeed. China cannot be written out of the global story, much less the Asian story. At best, a few boulders can be rolled into its path.

velloor@sph.com.sg