Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Amartya Sen gave an exclusive interview to our Web Editor Naomi Canton ahead of his speech and Q+A session at Asia House on 30 June 2014.

Renowned Indian economist and Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen says the Indian Government has not invested adequately in education and healthcare for its citizens and doing so is the only way for India to sustain economic growth.

The comments by 80-year-old Dr Sen, who was born in West Bengal in British India and who won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998, counter the argument by many in India who believe that investing in infrastructure, creating jobs, increasing energy supplies and focusing on industrial growth, are the way forward.

India has seen its economic growth drop from an average of more than 8.5 per cent between 2003/4 and 2009/10 to 4.5 per cent in 2012-2013 and 4.7 per cent in 2013-2014.

But Sen, who studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, does not believe that a focus on building infrastructure, providing power and easing regulations, will solve India’s problems. He believes the “development of human capability” is fundamental to economic growth, that good quality healthcare should be available to all Indian citizens and there should be a focus by the Government on achieving 100 per cent literacy among the population.

After the interview Sen gave a speech at Asia House about what India has failed to learn from the Asian experience. Many representatives of the Indian media were present. They included The Hindustan Times which ran a story following the event titled Modi has every right to rule: Amartya Sen. CNN-IBN ran a similarly titled story which can be read here. BBC Radio Four’s The World Tonight ran this.

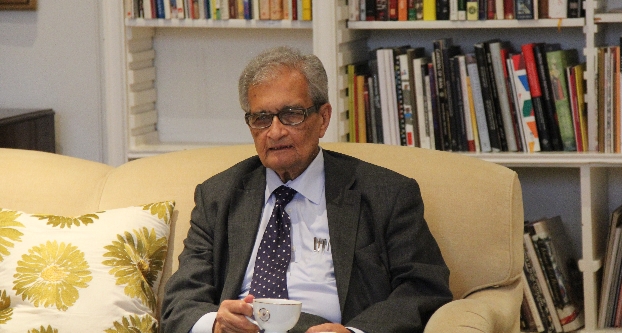

Amartya Sen chatting on the sofa of the Asia House Library

Narendra Modi’s BJP party won the 2014 Indian general election with an outright majority on the platform of promising jobs, infrastructure and economic growth. Dr Sen was an outspoken critic of Modi’s policies before the election. In his interview at Asia House he said: “He was not my favourite candidate, people know that, but he has now won. India is a democracy and so he has the right to govern. He has not yet announced his policies, so we will have to examine them and if we have some critical things to say on that, then that should be based on understanding of what he is announcing that he will do, rather than expectation of what he will do, as that would be very unfair to him.”

When pushed on what he feels the one thing Modi must do to revive India’s battered economy, he said: “I don’t think there is only one thing, but basically there is an approach, namely the approach has to be, that there is nothing as important both for spreading the fruits of economic growth and making it sustainable and to enhance it, than the development of human capability and that requires educational expansion and healthcare, both of which are in a mess in India and it’s not much better in Gujarat,” he said in an apparent dig at the BJP and Modi supporters who have always hailed the western state of Gujarat, which Modi was Chief Minister of until he became Prime Minister of India in May 2014, as an example of a highly developed state which they say has seen fast economic growth, good infrastructure and prosperity and is a state the rest of India should emulate.

Asia House Web Editor Naomi Canton interviewed Amartya Sen

Sen, who currently teaches philosophy, mathematics and economics at Harvard University, said he was more impressed with the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Himachal Pradesh.

“Once among the poor Indian states, these three states which have focused on education and healthcare, are now among the top five Indian states in terms of per capita income, in addition to being among the top states in life expectancy, low mortality, low fertility and so on – that’s the line in which I think Indian policy has to be reshaped – and I hope that’s what the present government will do,” he said.

Sen, an Indian citizen who currently lives in the USA, has worked abroad since 1971 but remains outspoken on Indian affairs. When asked why he does not live in India, he said: “Mainly because I teach at Harvard, so I have to live in the USA. When I taught at Delhi University, I lived in Delhi. When I taught at the LSE in London and Oxford I lived in England, so it depends on that.”

Not all Indians agree with Sen’s views however. A BJP leader Subramanian Swamy once described him as “not Indian in the proper sense of the word” after Sen said, before the 2014 election, that he did not support Modi.

Sen was born in Santiniketan on the campus of Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University, which is in present-day India. His family is from present-day Bangladesh and he spent much of his childhood in Dhaka.

When asked why the urban middle classes in India appear to be not bothered about the hundreds of millions of their fellow citizens living in poverty, he said: “This is because the relatively prosperous section of India, which numbers approximately 200 to 300 million, their lives do improve with the per capita income going up – whether or not schools exist and hospitals see patients – because they manage alright on the basis of their superior income ability. But that is no reason why they should not worry about others,” he said.

Since Independence, India has not suffered any famines and Dr Sen, who has done a lot of research on the causation and prevention of famines, puts this down to democracy and the fact the Indian public and the free media would not tolerate it. Millions of Indians died in the Bengal famine of 1943 which took place under the British rule of India, for example.

“After India became a democracy, people sympathised with famine victims in a way they have not before, but they have not had that noticeable amount of feeling towards the people who get a very bad school or no school at all, or very bad medical care,” he said.

As for how to achieve poor inclusive and sustainable economic growth in India, he said: “There is nothing as good for sharing and sustaining economic growth than having an educated healthy labour force. The education in schools in India is very bad and there are not enough schools and the hospital system is very badly organised,” he said, adding this was all covered in his book An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions (2013).

Regarding the ‘Modi fever’ boosting the Nifty and Sensex to record highs, Dr Sen said: “You would expect that.” But as for whether it is sustainable, he said: “That will depend on what happens next.

“It is not surprising the Indian stock market is booming at this stage a month after the election, but the difficult days are yet to come.

“But the stock market is only one way of judging things,” he added. “There are other indicators such as people’s life expectancy, mortality rate, literacy rate, ability to read and write and count and calculate.

“India’s performance in the competitive test like PISA is dreadful,” he said, referring to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests.

As for whether India is seeing the right levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) right now, he said: “We don’t know that. It depends on what the competition of that is. FDI can be very useful sometimes and sometimes it is not, you can’t generalise about FDI,” he said.

“In education and healthcare, there is a lot that one can do in international collaboration,” he concluded. “I think mainly giving jobs and creating employment is very important.”

Amartya Sen looks pensive enjoying a cup of tea inside the Asia House Library

To listen to the audio of the interview, click below:

Dr Sen also gave a speech about what India has failed to learn from the Asian experience and then answered questions from the audience. The audio can be listened to below:

To see a slideshow of the event click below:

To watch the video of Amartya Sen’s speech click below:-

Keep an eye on the What’s On section of this website here for more stimulating discussions like this.

Have you considered membership of Asia House? Click here for more details.