Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Corrected August 14 2024 – adds Theresa Coffey visit*

By Matilda Buchan, Research Analyst.

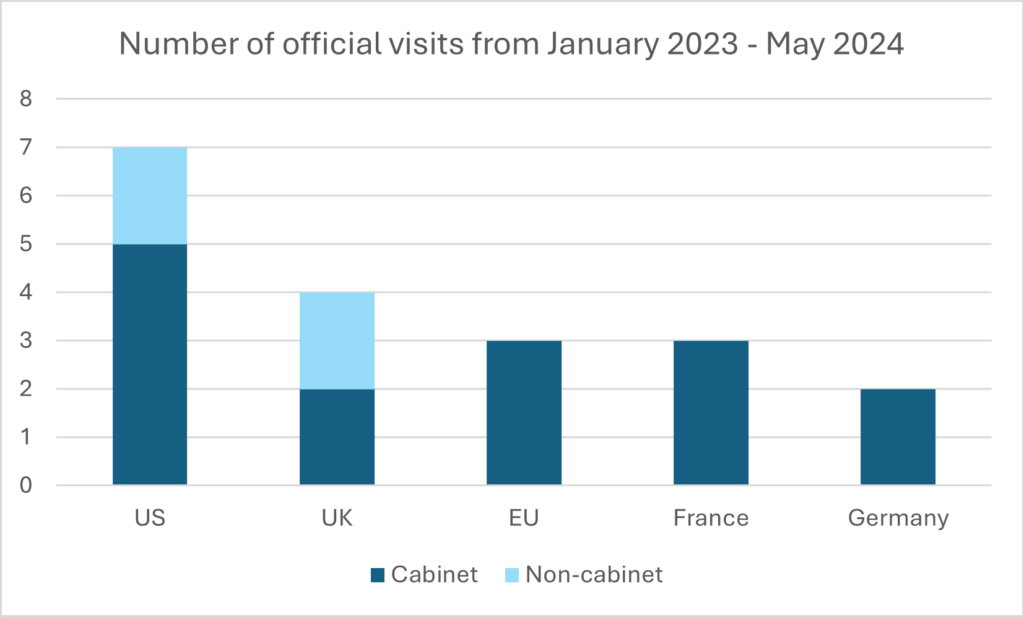

“No significant global problem – from climate change to pandemic prevention, from economic instability to nuclear proliferation – can be solved without China”.[1] These are the remarks of former UK Foreign Secretary, James Cleverly, and reflect international recognition of China’s global significance and the necessity of engagement. Yet, foreign policy and official engagement with China is becoming increasingly inconsistent as politicians struggle to balance economic ties with concerns surrounding national security, human rights issues, and supply chain dependencies. The US has demonstrated a constructive engagement strategy despite tensions; since the start of 2023, there have been seven official visits, including five at cabinet level, allowing for collaboration on economic matters and dialogue on issues of contention. Of our sample, the UK follows with a total of four visits, with two at cabinet level, ahead of the EU and France with three visits each over the same period. For France, this included a state visit by President Macron and an opportunity to actively engage and signal a desire to stray from current EU policy and strengthen its bilateral ties, which has been welcomed by China. Germany is just behind with two visits, albeit by senior figures including Chancellor Scholz, and German rhetoric towards China has been at times critical and robust but also inconsistent, creating an uncertain policy environment for businesses to navigate.

Figure 1 – Number of official visits from January 2023 – May 2024[2]

The US, EU, France, Germany and the UK all view China in a similar light, albeit to varying degrees, recognising it as both a crucial economic partner and a challenge to the global order. The naming of most countries’ regional strategies has changed from Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific, which place more emphasis on India and the Indian Ocean to balance China’s influence. The US, EU and the UK all summarise their approach using triplet phrases; “invest, align, compete”, “promote, protect and partner” and “protect, align, engage”, respectively. These aim to reduce complex and rapidly evolving policies down to concise and seemingly digestible approaches. France exemplifies the greatest divergence within the sample, as it has not published a China-specific strategy. Instead, government actions and rhetoric indicate a preference for deepening economic ties, in contrast to the derisking approach of the EU, Germany and UK, and the active pursuit of decoupling by the US.

US Secretary of State Blinken, who has visited China twice since the beginning of 2023, has described the US’ relationship with China as “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be […] the common denominator is the need to engage”.[3] Indeed, the high frequency of engagement has enabled the US to execute a balanced approach. Secretary Blinken met with President Xi in June 2023 and raised concerns surrounding unfair economic practices, human rights violations and stability across the Taiwan Strait.[4] Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, has also visited China twice over this period and raised concerns about Chinese overcapacity.[5] Contrastingly, Secretary of Commerce, Gina Raimondo, adopted a more collaborative approach on her visit, stating a “strong Chinese economy is a good thing” and “the vast majority of our trade and investment relationship does not involve national security concerns”.[6] The US effectively distinguishes between economic strengthening and decoupling and executes this through official visits where specialised politicians engage on specific areas of expertise. This has fostered the establishment of commercial working groups and regular ministerial meetings, aiding long-term engagement on mutual interests.

The UK undertook a major review of its foreign policy under the Integrated Review in 2021 and 2023 which highlighted the multiple challenges that China poses. Yet a clear and consistent policy direction is lacking, stemming from the high turnover of prime ministers and foreign secretaries, each with differing views. Former Prime Minister Liz Truss was reportedly planning to re-categorise China as a “threat”, which Rishi Sunak and then Foreign Secretary James Cleverly resisted.[7] Prior to his visit in in August 2023 (the first by a foreign secretary in over five years) Cleverly said “we must engage with China where necessary and be unflinchingly realistic about its authoritarianism”.[8] However, since then, only one other cabinet-level visit has taken place. Thérèse Coffey, then Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, visited in November 2023, although her visit received very little media attention. She resigned from the cabinet just a few days after returning from China ahead of a reshuffle by then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Two junior ministers, Anne-Marie Trevelyan, Minister of State for Indo-Pacific and Lord Johnson, Minister of State for Investment, also visited China, but those visits also attracted very little attention. The Commons Foreign Affairs Committee criticised the government’s current approach to China and called for publication of the unclassified China-specific strategy, as well as for the provision of sector-specific guidance for industries of critical national importance, in order to provide clarity. The committee Chair stated “it is more important that we are in the room with them in stark disagreement, rather than cutting off relations”.[9][10] This limited engagement has stalled diplomatic progress and creates an uncertain policy environment for businesses.

The EU aims to enforce a unified approach towards China and Ursula von der Leyen favours de-risking as opposed to the US’ approach of decoupling. However, there are vast differences across the EU’s bilateral relationships with China, in terms of trade balances, sectoral competition and exposure of critical sectors. Therefore, there has been a different mix of policy approaches and official visits across EU members.

Germany supports the EU’s de-risking approach and, in some respects, takes a harsher stance but engagement has been inconsistent. Germany’s automotive sector is exposed to China’s and their strategy highlights human rights abuses and economic dependencies yet acknowledges the importance of engagement: “systemic rivalry with China does not mean that we cannot cooperate”.[11] Chancellor Scholz visited China in April 2024 and was joined by senior figures from Mercedes-Benz and BMW. Speaking in Shanghai, Scholz commented “at some point there will also be Chinese cars in Germany and Europe […] competition must be fair”.[12] This followed a trip the previous year by Minister for Foreign Affairs, Annalena Baerbock, who described the visit as “more than shocking” and referred to President Xi as a “dictator”.[13] Shortly after, the finance minister’s scheduled visit was cancelled. Hence Germany’s limited engagement has had mixed outcomes; the foreign minister’s comments led to the summoning of the ambassador, while Scholz aimed to refocus discussions on the economic relationship. As the EU proceeds with its investigation of Chinese electric vehicle subsidies, Germany would benefit from diplomatic engagement that carefully manages the economic relationship to avoid hostile reactions.

France strays from the EU’s prescription of wanting to de-risk from China, instead wanting to deepen economic ties. President Macron has also warned of the risk of the US’ influence, asking “is it in our interest to accelerate [a crisis] on Taiwan? No. The worst thing would be to think that we Europeans must become followers on this topic.”[14] France’s unique approach has been welcomed by the Chinese. During President Macron’s state visit, which he invited EU President von de Leyen on, Macron was greeted by China’s foreign minister on the red carpet accompanied by military parades, while von de Leyen was greeted by the ecology minister at the regular passenger exit.[15] Two French ministers have visited since. Former Minister for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Colonna, discussed the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, a sensitive topic handled diplomatically as her counterpart Wang Yi commented on a “positive trend of Sino-French cooperation on all fronts”.[16] France has not published a China specific strategy, but the official visits and rhetoric have allowed France to communicate its desires for stronger economic ties while also expressing foreign policy concern.

No Western country has a straightforward relationship with China. Most China strategies highlight its economic significance while also raising concerns surrounding human rights violations, national security and trade dependencies. Official visits are an important tool that allow governments to engage and take action on risks and areas of opportunity. They require huge resource commitments, but they signal diplomatic intentions, garner international media attention and lead to the establishment of working groups and recurring engagement. The US exemplifies how a high frequency of official engagements can help to deepen economic ties in areas of mutual interest, while raising concerns and communicating decoupling strategies. As the UK, EU and US approach their 2024 elections, it is likely that there will be, potentially significant, changes to the cabinets and foreign policy. To maintain diplomatic ties, it is crucial that engagement and official visits are prioritised. In the UK, Labour lead in the polls ahead of the 4 July election, and thus far have emphasised the desire to deepen ties with the EU. If victorious, Labour will need to quickly establish their approach to China, the UK’s third largest trading partner after the EU and US, and provide clear guidance to UK businesses integrated in Chinese supply chains.[17]

* Thérèse Coffey visited China on 7 November 2023, just days before she resigned from the cabinet during a reshuffle by then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. This was omitted from the original version of the report. The report has been updated to include reference to that visit.

Annex – high-level visits to China from January 2023 to May 2024 [18]

| US | UK | EU | France | Germany |

| Anthony Blinken, Secretary of State – June 2023 | James Cleverly, former Foreign Secretary – August 2023 | Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission – April 2023 | Emmanuel Macron, President – April 2023 | Annalena Baerbock, Minister for Foreign Affairs – April 2023 |

| Janet Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury – July 2023 | Lord Dominic Johnson, Minister for Investment, August 2023 | Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission – December 2023 | Catherine Colonna, Former Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs – November 2023 | Olaf Scholz, Chancellor – April 2024 |

| John Kerry, former Special Presidential Envoy for Climate – July 2023 |

Thérèse Coffey, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs – November 2023 |

Charles Michel, President of the European Council – December 2023 | Stéphane Sejourné, Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs – March 2024 | |

| Gina Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce – August 2023 | Anne-Marie Trevelyan, Minister of State for Indo-Pacific – April 2024 | |||

| Marisa Lago, Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade – January 2024 | ||||

| Janet Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury – April 2024 | ||||

| Anthony Blinken, Secretary of State – April 2024 |

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/foreign-secretary-visits-beijing-to-further-british-interests#:~:text=Foreign%20Secretary%20James%20Cleverly%20said,can%20be%20solved%20without%20China.

[2] Officials are categorised according to their position at the time of the visit. The categorisation of officials varies by country and they have been split into “cabinet” and “non-cabinet” to analyse the differences across the sample.

[3] https://www.state.gov/a-foreign-policy-for-the-american-people/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/19/antony-blinken-xi-jinping-beijing-china#:~:text=The%20US%20secretary%20of%20state,aimed%20at%20stabilising%20spiralling%20relations.

[5] https://www.reuters.com/graphics/CHINA-USA/TRADE/zdvxneaaxvx/

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/86a43671-211e-4599-99b2-40507aef4e68

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-66651355

[8] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/our-position-on-china-speech-by-the-foreign-secretary

[9] https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/78/foreign-affairs-committee/news/197226/foreign-affairs-committee-reviews-governments-tilt-to-the-indopacific/

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-66651355

[11] https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_report_2023_final_1.pdf

[12] https://www.euronews.com/business/2024/04/19/scholzs-visit-to-china-balancing-distance-and-diplomacy#:~:text=The%20German%20chancellor%20Olaf%20Scholz,unveiled%20its%20%22China%20strategy%22

[13] https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germanys-foreign-minister-parts-china-trip-more-than-shocking-2023-04-19/

[14] https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-china-america-pressure-interview/

[15] https://www.politico.eu/article/china-divide-rule-eu-france-unity-ursula-von-der-leyen-emmanuel-macron-xi-jinping/

[16] https://www.rfi.fr/en/international/20231124-france-counting-on-joint-efforts-with-china-to-resolve-gaza-ukraine-conflicts

[17]https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/balanceofpayments/datasets/uktotaltradeallcountriesseasonallyadjusted

[18] Desk-based research. Cabinet-level equivalent in bold.

Asia House is working with governments across Asia, the Middle East and the West, as well as multilateral organisations and the private sector to drive commercial and political engagement around key issues in global trade. For more information on our research and programmes, please contact Katie Reid, Stakeholder Engagement Associate via katie.reid@asiahouse.co.uk

*European Union copyright images are reproduced under Creative Commons licence.