Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Leaders of 15 Asia-Pacific economies – the ASEAN 10 plus Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea – signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) on Sunday 15 November, creating the world’s largest economic bloc. Asia House Advisory provides a guide to the deal.

The 15 RCEP economies together make up 30 per cent of the world population and just under 30 per cent of global GDP. The agreement notably no longer includes India, which dropped out in November 2019, but the deal leaves the door open for New Delhi should they wish to join in the future.

Signatories hope that the agreement will boost trade across the bloc by lowering tariffs, standardising customs rules and procedures, and widening market access. According to the Brookings Institution, RCEP has the potential to grow global real incomes by US$285 billion annually if put into place before 2030 – which, in absolute gains, could be twice that of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (CPTPP).

RCEP’s origins are in an attempt to harmonise ASEAN’s agreements with its key trading partners though the project grew into a major trade expansion exercise for ASEAN and six neighbouring economies. The negotiations have been tricky throughout due to divergent goals, diversity of the economies taking part, and external factors, not least the US-China trade war and geopolitical tensions. There was a tension between a tariffs and goods-based agreement favoured by economies including China, and a ‘high quality’ agreement favoured by the more advanced economies of Japan, Australia and New Zealand. The lack of alignment from the outset has resulted in protracted negotiations and perhaps less ambitious targets overall. After causing significant delays, India eventually dropped out of the agreement (see below) although the door still remains open for them to join.

The final agreement is substantial and will drive trade in the region, lowering trade barriers at the border and improving the in-market regulatory environment. The agreement’s 20 chapters cover tariffs, rules of origin, digital aspects, intellectual property, and provide a framework for future negotiations and updates.

RCEP is expected to primarily benefit goods trade by reducing tariffs, and most critically for supply chains, creating common rules of origin in the bloc. This will allow companies to ship products between RCEP countries without needing to worry about specific rules of origin criteria. Most significantly, this means that companies can make products in any RCEP country and be able to ship to any of the 15 RCEP with a single certificate of origin. This will reduce trade costs for companies and could further encourage multinationals to establish supply chains within the bloc. The regionalisation of supply chains has been on-going for some time, driven by changing patterns of demand and input costs, and a greater integration of risk into supply models. Global trade tensions driven by the US-China trade war and the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic have further supported a regional model, enabled and reinforced by regional agreements such as RCEP.

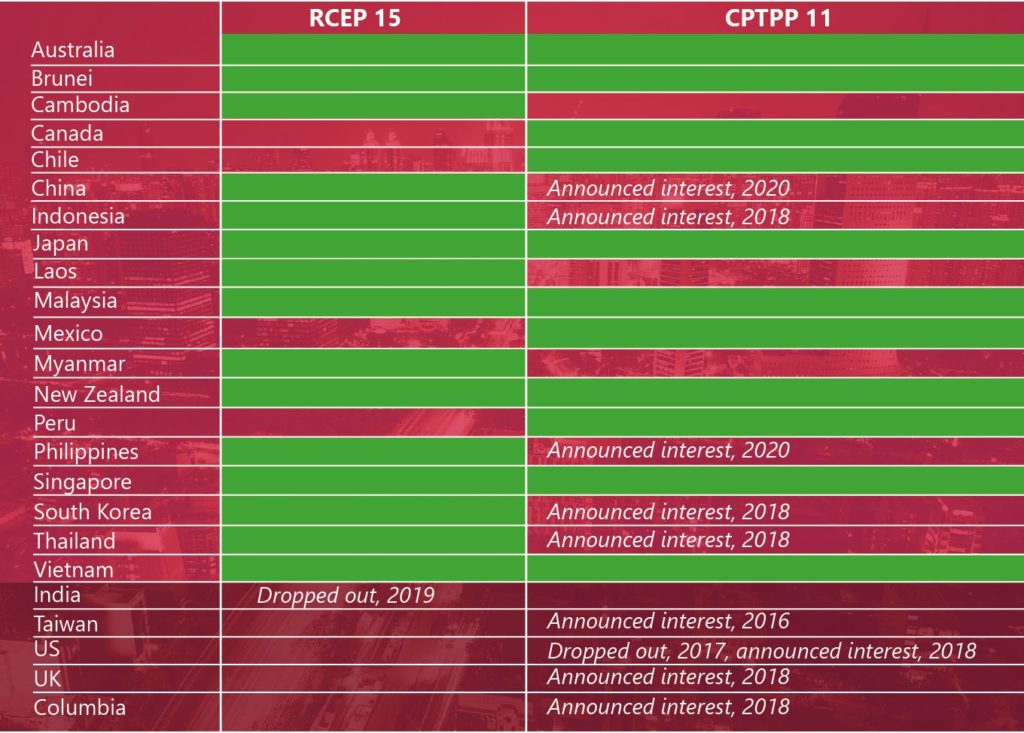

A simplistic interpretation has been that RCEP is a China-led agreement developed as a counterbalance to the CPTPP which is driven by close US ally Japan – the CPTPP’s precursor, the TPP, was originally driven by the US itself. This analysis broadly falls apart on contact with reality, not least because Japan is a member of both agreements – the blocs share a total of seven members – and China announced its interest in joining the CPTPP earlier this year. The CPTPP has a much broader geographic scope – including economies in the Americas (Canada, Chile, Mexico, Peru) and possibly Europe (UK), whereas RCEP’s foundations are firmly in Asia, being based around ASEAN and its key trading partners. However, it is true that China has been a big supporter of the agreement, and broadly its goods and tariffs preferences have been borne out.

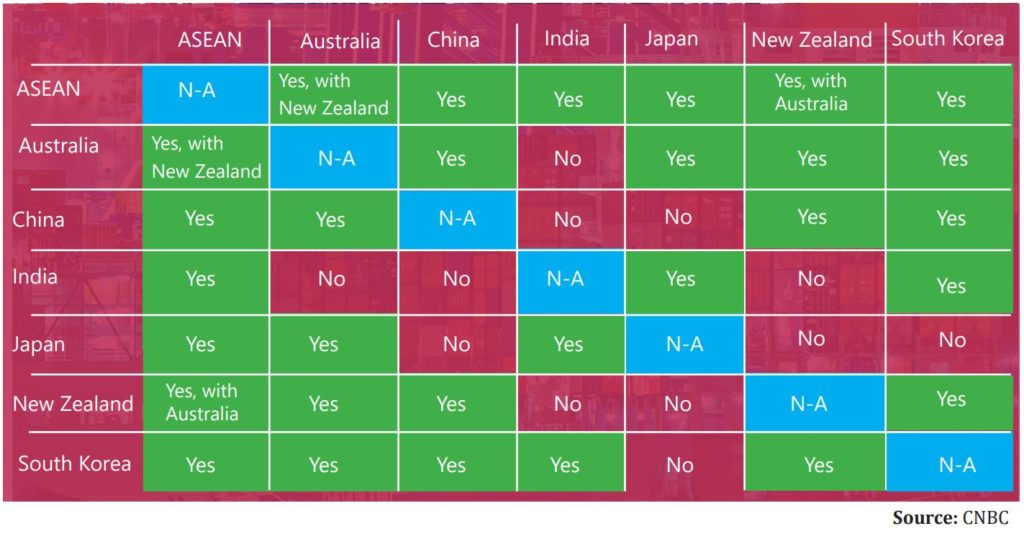

In reality, ASEAN has been the real driver from the beginning, with the agreement based around a ‘cooperation agenda’ with more developed trading partners supporting the (generally) less-developed ASEAN economies. As mentioned above, the agreement is based on ASEAN’s FTAs and ASEAN and its economies have played a major role driving negotiations. In geopolitical terms, the agreement positions ASEAN at the centre of the Asia Pacific region. The agreement could be seen as an example of ASEAN’s refusal to choose between Chinese and US spheres of influence. The agreement also provides cover for other trade corridors that would be politically more challenging outside a plurilateral agreement – Japan-China and Japan-Korea trade for example.

In reality, ASEAN has been the real driver from the beginning, with the agreement based around a ‘cooperation agenda’ with more developed trading partners supporting the (generally) less-developed ASEAN economies. As mentioned above, the agreement is based on ASEAN’s FTAs and ASEAN and its economies have played a major role driving negotiations. In geopolitical terms, the agreement positions ASEAN at the centre of the Asia Pacific region. The agreement could be seen as an example of ASEAN’s refusal to choose between Chinese and US spheres of influence. The agreement also provides cover for other trade corridors that would be politically more challenging outside a plurilateral agreement – Japan-China and Japan-Korea trade for example.

India withdrew from RCEP in November 2019 with Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar saying that ‘no agreement was better than a bad agreement’. India’s main concerns revolved around sections on market access and trade imbalances in industrial and agricultural trade. Fears of market access for more competitive goods from China was at the root of many of the concerns. India has trade deficits with 11 of the 15 economies– and calculated that the deal would exacerbate the situation. However, provisions that specifically address India will simply be frozen, and the agreement will remain open for India to re-join at any time.

This briefing was produced by Asia House Advisory. For more information about the consultancy and research services provided by Asia House Advisory, please contact Ed Ratcliffe, Head of Advisory: ed.ratcliffe@asiahouse.co.uk

To receive analysis like this directly to your inbox, subscribe to our mailing list.