Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Following the recent European Economic Security Strategy whitepaper, Zhouchen Mao, Head of Research and Advisory at Asia House, identifies key trends in the EU-China relationship and analyses the key role of trade relations between the two economies.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT ASIA HOUSE RESEARCH

Asia House Analysis

Key messages:

EU’s ambiguous China strategy

EU-China relations evolved considerably in the first half of 2023. Despite a flurry of high-level diplomatic engagements between the two sides, substantial changes to the EU’s China policy were being finalised. In June, while recognising the importance of economic relations with China, the European Commission and Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, jointly published an Economic Security Strategy[1] that outlined details of plans to reduce supply chain risks and restrict trade and investment flows in the high-tech sector[2].

In principle, the release of the strategy paper signalled the EU’s intent to recalibrate its trade relations and align closer with the US on China policy. But in practice, the changing international system, the EU’s strong economic ties with China, and divergent interests among member states will complicate steps towards achieving the goal.

Firstly, the growing strategic competition between China and the US is shaping the EU’s own geopolitical calculation. Mindful of the need to balance its economic ties with China and the longstanding partnership with the US, the EU has so far sought to position itself as a separate pole. It is pursuing a policy defined by cooperation with China in areas of mutual benefit, but also one of competition and “strategic autonomy” – the latter essentially translating as the EU acting on its own and not being overly reliant on the US.

Some distrust has grown between the US and the EU in recent years, which deepened substantially following the election of former President Donald Trump[3] and the passage of current President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. The latter, with its US$369bn in subsidies, is seen as disadvantaging EU companies.

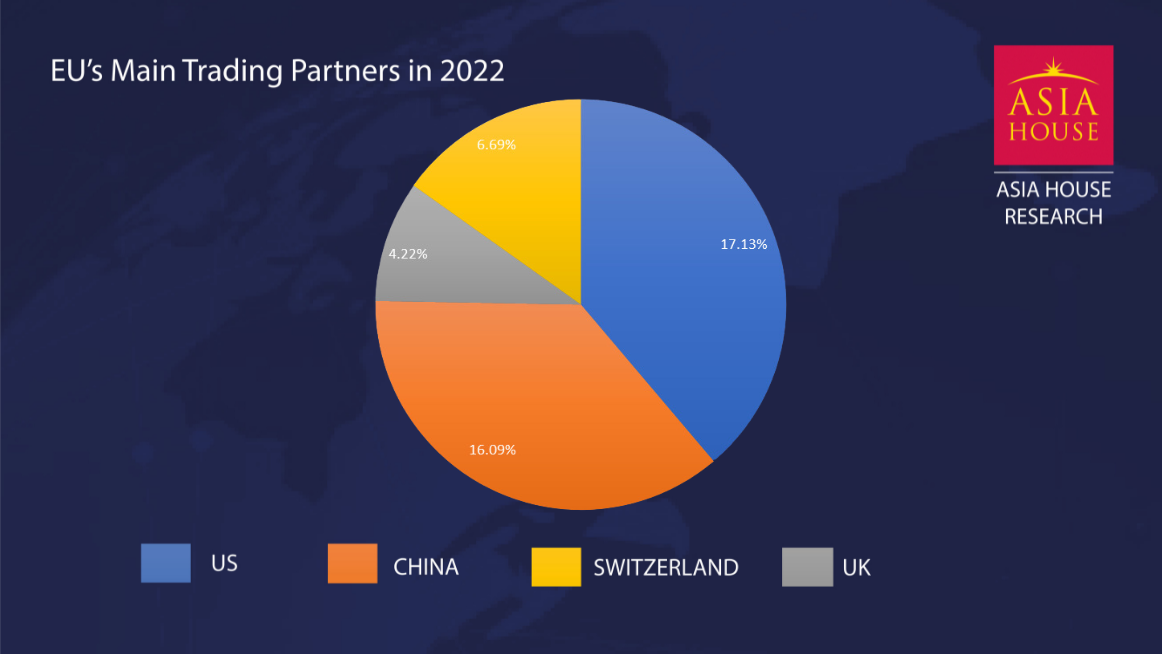

Secondly, the EU is more exposed to trade with China than the US, making restrictions and inward-looking policies more costly. Accordingly, there is less political will to reduce economic relations with China. In 2022, the EU’s total trade of goods and services with China reached approximately US$850bn, making Beijing its second largest trading partner after the US. The EU is also heavily dependent on China for critical components and technologies to power its green transition.

Thirdly, there are doubts whether member states are ready to embrace a tougher China policy due to divergent interests. Some members want to focus on economic relations, while others prefer to prioritise political, security, and/or human rights issues. Ultimately, implementation of any trade and investment restrictions is a member-state prerogative – and the bloc’s two largest economies, France and Germany, are reticent.

In Germany, China has moved to the centre of political debate in recent years. In July, the ruling coalition government published it much-awaited China Strategy[4]. The document struck a hawkish tone but at the same time outlined a balanced approach that called for both “de-risking”[5] and cooperation.

Sino-German relations are primarily business-driven and transactional. China is a major market with thousands of German companies operating in the country. On bilateral trade, China is the fourth largest destination for German exports at 6.2 per cent, while Chinese products accounted for around 12 per cent of all German imports. Specifically, Germany imported about two thirds of rare earth elements, many of which are indispensable in batteries, semiconductors, and electric vehicles.

In light of significant invested trade and business interests in China, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz recently suggested that “de-risking” should be a matter for companies with the government taking a limited role. Scholz’s comment reflects both his pro-business position and concerns that federal government “de-risking” would undermine the economy, in which critical sectors such as automotive and machinery rely extensively on the Chinese market.

The implementation of this China Strategy is likely to be selective as the Chancellor has a final say in the overall direction of Germany’s foreign policy. Scholz’s Social Democratic Party has ensured the new strategy remains broad and not overly restrictive. For instance, the document did not outline any specific incentives nor binding requirements for businesses to diversify from China. Neither did it offer compensation for businesses to do so, or penalties for firms that do not.

France, on the other hand, is less dependent on the Chinese market, with major French companies such as Carrefour and Auchan divested, and other firms having re-adjusted their supply chains following disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, total bilateral trade between France and China reached approximately US$81.23bn, a decline of 4.5 per cent (US$3.84bn) from year before.

The French economy is largely exposed to China through luxury goods, cosmetics, tourism, and infrastructure projects, rather than through the industrial and tech sectors that are likely to be targeted by EU restrictions. Yet, French President Emmanuel Macron has reportedly asked the EU to slow its “de-risking” push.

Macron’s state visit in April to China rekindled these discussions as Paris explicitly cautioned against becoming “just America’s followers”[6].

For multinational corporations, economic ties with China will remain robust in the coming years. Businesses will continue to view China as a lucrative market with vast opportunities, especially if firms can find the niches that align with Beijing’s development strategy.

However, the key concern going forward is centred on how EU firms operating in China can mitigate growing geopolitical risks. The possible return of a Republican to the White House in 2024 could heighten the risks of additional sanctions, restrictions, and export bans, further impacting EU businesses. Moreover, transatlantic alignment on security concerns related to China – over access to high-tech, for example – could gradually deepen, which in turn would expose companies to risks of Chinese retaliation. But given the mutual interests to maintain functional economic relations, there remains opportunities for European firms to consolidate their position in China.

NOTES

[1] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52023JC0020

[2] The economic security strategy identified four concerns and risks in economic ties: disruptions to critical infrastructure, supply chain resilience, economic coercion, and the transfer of technology.

[3] Former President Trump imposed tariffs on EU steels and aluminium, criticised the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO)

[4] https://china.diplo.de/blob/2608638/49d50fecc479304c3da2e2079c55e106/230713-china-strategie-data.pdf

[5] De-risking is a term gaining increased use since the G7 countries used it as an alternative to the more radical “de-coupling. Despite the ambiguity around the term, it essentially means keeping most business going, but cautiously. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/words-and-policies-de-risking-and-china-policy/

[6] https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-china-america-pressure-interview/amp/