Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe

The Middle East Pivot to Asia is an annual Asia House flagship publication that tracks the growing economic and political connections between the Gulf and Asia. The 2024 report presents Asia House’s latest research on trade and investment trends between the Gulf and Asia.

The Middle East Pivot to Asia will continue to power ahead in 2025, despite a 12 per cent drop in the value of trade in 2023, due primarily to sharply lower oil prices. This report provides the latest insights into the key bilateral relationships driving the Pivot, including Saudi-China, UAE-India, Hong Kong-Gulf and Gulf-ASEAN partnerships. It also offers detailed analysis of Gulf-Asia cooperation, deal-making and investment in critical non-oil sectors including AI, renewable energy, advanced technologies, construction, and infrastructure over the past year.

Produced by Asia House’s Middle East Programme and sponsored by HSBC, the report aims to help business leaders and policymakers better understand this pivotal shift in global trade, which will have far-reaching economic and geopolitical implications. The report includes interviews with key business leaders and policymakers in the Pivot, including:

Key Findings

Outlook

Executive Summary

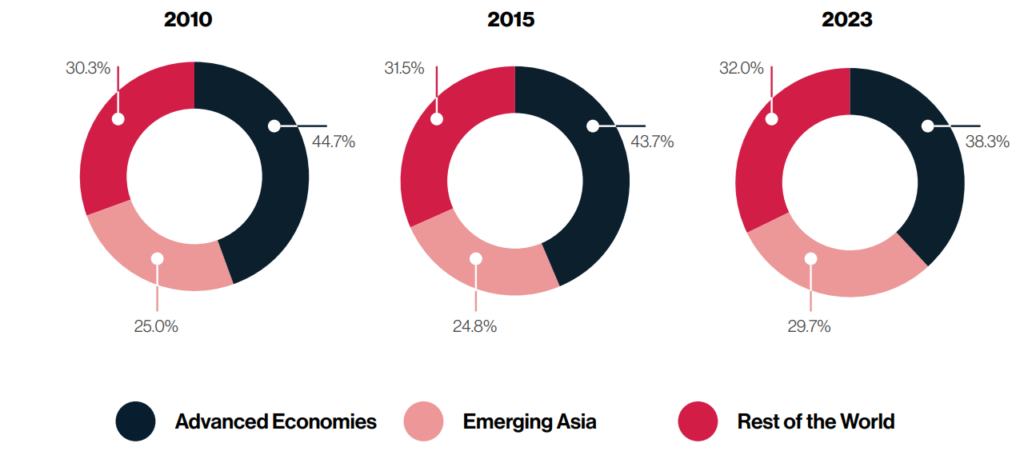

After several years of accelerated Gulf-Asia trade growth, 2023 saw a correction, driven primarily by a 17 per cent drop in oil prices. Trade value fell by 12 per cent from a record US$512 billion in 2022 to US$451 billion in 2023. However, the IMF forecasts that Emerging Asia economies will expand 5 per cent in 2025, partly because of a growing middle class. This is likely to drive sustained demand for traded products, though fluctuations in oil prices will continue to have an impact. While Gulf-Emerging Asia[i] trade has diversified into non-oil sectors, hydrocarbons still make up more than half of the total.

Despite the drop in value, Gulf-Emerging Asia trade remains at historically high levels, and there has been growing deal-making and investment between key Gulf and Asian powers in 2024 – suggesting the trend of increasingly close economic and commercial ties continues apace.

Gulf and Asian decision-makers and business leaders increasingly recognise the geopolitical and geo-economic significance of the Middle East Pivot to Asia and are seeking to capitalise on it. In 2024, there have been important deals signed, high-level bilateral political exchanges, further investment by Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) in Asia and more Asian firms expanding into the Gulf. Non-oil sectors in the Gulf, in particular, are receiving this investment, boosting future growth prospects.

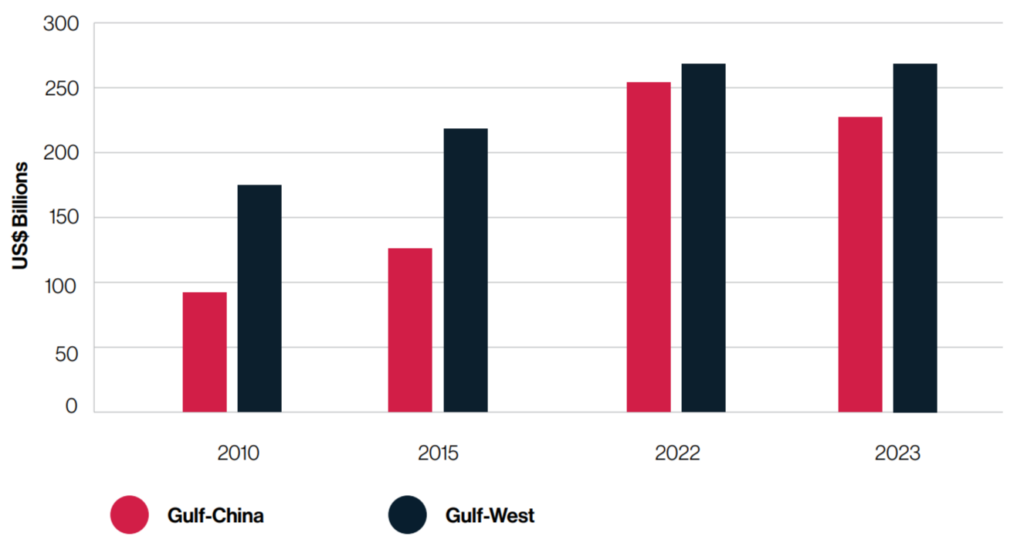

The gap between Gulf-Emerging Asia trade and Gulf trade with Advanced Economies[ii] has narrowed from US$193 billion in 2010 to US$82.3 billion in 2022. But despite the fact that the West (US, UK and Euro Area) is less dependent on Gulf hydrocarbons than Asia, Gulf trade with Advanced Economies proved resilient. It decreased by only 2.1 per cent between 2022 and 2023, compared with a 12 per cent fall in trade with Emerging Asia, widening the gap to US$131 billion.

Emerging Asia’s increased importance to Gulf trade over time

Still, long-term growth trends favour Gulf-Emerging Asia trade. The largest economies in both regions enjoy good immediate and long-term prospects. Gulf economic diversification is driving non-oil growth, creating opportunities for Asian firms in construction, infrastructure, technology, sustainability and financial services. The Gulf states’ economic and social reforms continue at pace, attracting Asian investment, firms and talent. New air routes between the Gulf and Asia will boost tourism and business connectivity. For these reasons, Gulf-Emerging Asia trade will keep growing and is on track to reach US$682 billion by 2030 if it continues at the 7.1 per cent average annual growth rate seen between 2010 and 2023.

The recent dip in trade has affected key Gulf-Asia bilateral partnerships. Saudi-China trade fell 7.6 per cent between 2022 and 2023, while UAE-China trade fell by 15.5 per cent. Despite this, both countries’ relations with China have deepened and grown more strategic. In 2023, Saudi Arabia and the UAE were invited to join the BRICS[iii] group of emerging economies, bringing them closer to Chinese strategic decision-making at a global level. The increasing use of the Renminbi (RMB) in international trade is also enhancing China’s economic influence. UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed’s visit to China in May 2024 cemented UAE-China cooperation across several areas and was the Pivot’s most significant bilateral political exchange of 2024. The Saudi-China corridor is again the largest in the Pivot, a distinction briefly held by the UAE-China corridor in 2022, and continues to enjoy considerable growth.

We expect Gulf-China trade growth to continue outpacing Gulf-West trade. Our projections suggest Gulf-China trade will overtake Gulf-West trade in 2027, growing from US$225 billion in 2023 to US$325 billion.

Gulf-China trade has caught up with Gulf-West trade over the decade

Some Gulf-Asia trade corridors have bucked the recent downward trend. Oman-Emerging Asia trade more than doubled from US$4.5 billion to US$11.1 billion between 2022 and 2023. Hong Kong-Gulf trade grew from US$13 billion in 2022 to around US$32 billion in 2023. Hong Kong has invested considerable political capital in bolstering ties with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee’s visit to these countries in February 2023 led to several significant deals and Hong Kong is working to position itself as a key hub for Gulf investment.

Despite the overall positive trend, there are some risks to the Middle East Pivot to Asia. Oil price volatility, the Middle East conflict and US-China tensions could all impact trade and investment. The Middle East conflict has worsened considerably over the past year, spreading from Gaza to Lebanon, Iran and Yemen. While Gulf-Asia commercial relations have been largely unaffected thus far, the conflict creates uncertainty for the region.

The incoming Trump administration could potentially impact the Pivot in several ways. The president-elect’s proposed tariffs on Chinese and global imports might undermine global trade but may also encourage closer economic ties between the Gulf and Asia. There is a risk, however, that his administration may pressure the Gulf to reduce cooperation with China, particularly in technology. In addition, a return of Trump’s previous “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran could intensify regional tensions.

Hydrocarbons remain crucial to Gulf-Asia trade. Asia has been the biggest consumer of global energy, and the Gulf is its primary supplier due to efficient shipping routes. Asian demand for oil is projected to continue on an upward trajectory through 2030 and beyond, which will have an impact on the Pivot. China’s oil consumption is expected to peak around 2030 but the world’s second-largest economy will remain a key market for Gulf producers for the foreseeable future. India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will become the largest drivers of oil demand growth past 2030.

Gulf investment continues to enhance both trade with Asia and cooperation in non-oil sectors. Partnerships in renewable energy and sustainable technologies are helping both regions achieve their climate goals, with several synergies unique to Gulf-Asia relations. Key areas of collaboration include solar power, green and blue hydrogen, ammonia and electric vehicles (EVs). China is the Gulf’s primary partner in these sectors, though Japan and South Korea have also become key partners over the last two years. The Gulf’s low-cost solar production is supported by China’s strength as a major manufacturer and exporter of solar panels. The Gulf is also investing to further its goal of becoming a blue and green hydrogen production hub, helping to decarbonise Asian industries. Meanwhile, Gulf targets for EV growth will likely generate an uptick in imports from China, the world’s largest EV producer. Green finance is essential to realising the Gulf’s energy transition, and we are seeing increased green bond issuances attracting Asian investor interest.

Other non-oil sectors benefiting from Gulf-Asia cooperation include technology, construction and infrastructure. AI is one thriving area, but this has been complicated by US-China tensions. US restrictions are limiting China’s access to advanced chips, undermining its AI development and prompting some Gulf firms to favour US technology. The Gulf states are seeking to strike a difficult balance between the two powers. We have seen increased cooperation in semiconductors as the Gulf works to boost its domestic production capabilities to improve supply chain resilience and to position itself as an alternative global supplier of chips. Asian firms remain central to various Gulf giga and construction projects, with Chinese companies leading the way in building ports, smart cities and other infrastructure.

Gulf SWFs continue to increase their focus on Asia, targeting not just returns but partnerships, Joint Ventures (JVs) and knowledge-sharing that can contribute to economic diversification and development. China and India continue to attract considerable attention, but developed Asian economies such as Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong are also receiving investment. While the US and Europe still account for the bulk of Gulf SWF assets, a growing shift towards Asia is reshaping global capital flows.

Indeed, another major trend is the influx of Asian wealth and asset managers establishing themselves in Gulf nations, particularly Dubai, to capitalise on the Pivot, the region’s economic diversification and growing pools of sovereign and private capital. This trend has been supported by a flood of High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNWIs) and Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals (UHNWIs) into the Gulf following social and economic reforms.

Gulf capital market expansion is attracting Asian money. The privatisation and listing of state-owned assets, particularly through Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), has become an important method of achieving Gulf economic diversification. Gulf privatisation represents a major opportunity for global banks and is generating fees for Asian and Western institutions alike. IPOs and cooperation between Gulf and Asian bourses to encourage cross-listings is another trend that will deepen Gulf-Asia capital market connectivity over the next few years.

The Middle East Pivot to Asia represents one of the fundamental geopolitical and economic shifts of our time. Both regions are increasingly entwined in one another’s growth. The Pivot will increase their importance to each other, reducing the role of Western perspectives in the strategic calculations of decision-makers on both sides. But the Pivot also represents a truly global opportunity that banks and financial services from across the globe can capitalise on.

This report was authored by Freddie Neve, Senior Middle East Associate at Asia House and Alana Li, Middle East Research Analyst at Asia House. Further written contributions were made by Elizabeth Heyes and John Kemp.

This report has been sponsored by HSBC.

For more information about Asia House’s Middle East expertise and research services, and to enquire about bespoke presentations on the issues covered in the report, please contact Freddie Neve, Senior Middle East Associate: freddie.neve@asiahouse.co.uk

[i] ‘Emerging Asia’ refers to the IMF’s ‘Emerging and Developing Asia’ list of 34 Asian economies, which includes China, India, and most ASEAN members but excludes advanced Asian economies such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand. Emerging Asia will hereinafter be referred to as Asia.

[ii] ‘Advanced Economies’ refers to an IMF list of 40 economies, including traditional GCC trading partners such as the US, UK, and Euro Area. Some Asian economies are included in this list, including Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand.

[iii] BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) is a regional bloc of developing economies.